Ask the Developer Vol. 20: Drag x Drive — Part 2

This article has been translated from the original Japanese content.

In this 20th volume of Ask the Developer, an interview series in which developers convey in their own words Nintendo's thoughts about creating products and the unusual details they hone in on, we're talking to the developers behind Drag x Drive™, a Nintendo Switch™ 2 game that launched earlier this year, on Thursday, August 14.

Check out the rest of the interview

Part 2: Three challenges, one solution

So, the core gameplay was starting to take shape. It had turned into a brand-new sport, with all sorts of elements mixed in. What kind of trial and error led you there?

Konishi: The controls for movement were starting to feel satisfying, and with tackles and quick turns, matches became more engaging. We then started thinking about how to give players more movement options. But that didn't mean any old moves would work. This game features unique analog controls, where players spin the in-game wheels using mouse controls, linking their physical movements to their in-game actions. We saw this analog feel as a key element to enhance their sense of immersion in the gameplay. To give in-game movements that analog feel, we defined two conditions that needed to be met. First, movements had to be something that could be done in real life without feeling unnatural.

Second, the player's mouse movements had to correspond clearly to their in-game actions.

Hamaue: In wheelchair basketball, there’s a technique called tilting, where one wheel is lifted off the ground. We realized that this would work well in the game and meet our conditions, since lifting one of the Joy-Con 2 controllers could correspond to that action. That’s how we ended up implementing it in the game. That said, we also wanted to add something more dynamic.

Konishi: We looked into real-world movements and considered implementing techniques like a wheelie, where the front wheels stay lifted while moving, and a 180-degree turn. But those ended up conflicting with other controls and didn’t quite deliver the analog feel we were aiming for. Then we came across a BMX technique called a bunny hop, where the rider first lifts the front wheel, then the rear, to hop. We thought that maybe a wheelchair could hop too, if you tilted to the left and then to the right in quick succession. So, we tried drafting a spec for it, but...

Hamaue: We couldn't find any reference material showing someone actually performing a bunny hop-like movement in a wheelchair, so we had trouble picturing what kind of arm movement would make the controls feel convincing. We also wanted the movements to feel natural, so we were cautious about implementing actions that don't exist in real life.

Konishi: So, I decided to give it a go myself. I got into a wheelchair and did my best attempt at a bunny hop. By quickly tilting left and right, I managed to lift off the ground by about 2 millimeters. (Laughs)

I documented it on video and showed it to Hamaue-san to convince him.

Hamaue: I wouldn't exactly call it a real-life movement, but the video helped me visualize it. (Laughs) Once we'd implemented the bunny hop, the addition of three-dimensional movement added new layers of strategy that didn't exist when the gameplay was restricted to two-dimensional movement. For example, being able to get rebounds more easily.

On the subject of jumping, one of the game’s distinctive features is the half-pipe under the goal, which players can use to launch themselves into the air and make stylish shots. Did that idea come up around this stage of development?

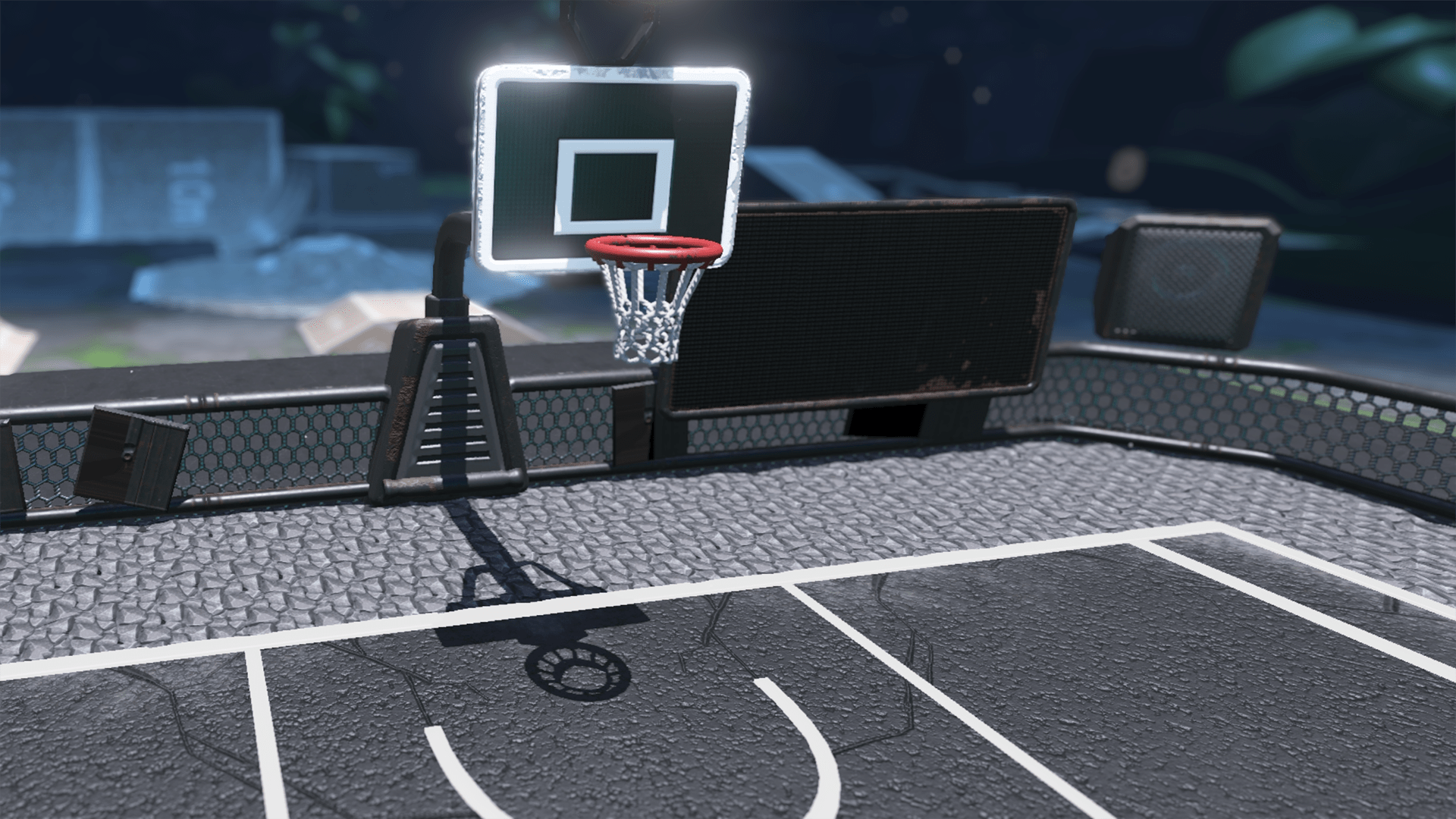

Konishi: Yes. One of the challenges we faced for a long time during development was figuring out what to do with the edges of the court. We went through a lot of different ideas.

Hamaue: At first, we placed walls around the edges of the court. But when we played proper matches with that setup, we noticed that players tended to avoid the center of the court and attack from the sides. That led to everyone crowding around the edges of the court, making it hard to move, and we realized it wasn’t going to work.

Konishi: Next, we tried removing the walls and added a rule where going out of bounds was penalized by losing possession of the ball. But that led to players focusing too much on pushing opponents out of the court. That shifted the core of the gameplay, which wasn’t what we wanted, so we scrapped that idea too.

Hamaue: Then we tried adding gravel around the court.

Konishi: That’s right. If a player left the court and entered the gravel area, they'd slow down, but wouldn’t drop the ball. That helped keep the significance of tackling to steal the ball. There are real-life street basketball courts with gravel around the edges, so we thought it wouldn’t look out of place. But then it turned out to be unfriendly to beginners. Beginners would often head straight for the goal, fail to turn after shooting, and end up hurtling right out of the court. They’d shoot and then immediately plunge into the gravel. Since they'd slowed down, they couldn’t get out quickly, even though the match was still going on. That frustrated players, so we ended up ditching the gravel idea as well.

Konishi: After anxiously deliberating our next steps, we resolved to place a half-pipe under the goal.

So here's where the half-pipe finally enters the picture.

Hamaue: Our team originally planned to split things up. Inside the court, the gameplay would focus on flat, two-dimensional movement. Outside the court, we wanted to create something with more three-dimensional movement, like wheelchair motocross. But then Konishi-san plonked a half-pipe right under the goal and said, “Here you go!”

Everyone: (Laughs)

Konishi: I ended up defying the plan our team had agreed on. And I was the director, too.

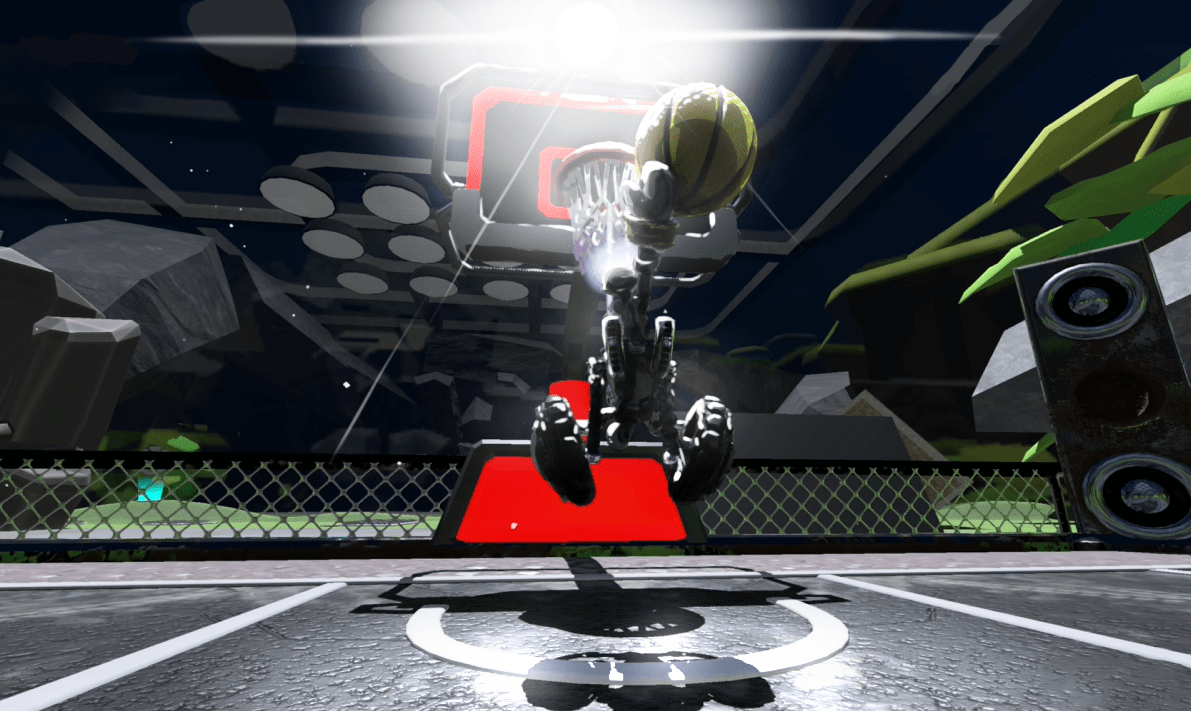

Hamaue: That's when the going got really tough... Introducing the half-pipe meant players could now launch themselves high into the air, adding airborne action to matches. (Laughs) We had to design and implement the physics for aerial tricks like catching the ball mid-air or performing a backflip shot. But once we'd built it, the extra three-dimensional movement made the game even more fun. So ultimately, I think it was a brilliant idea.

Konishi: It was tough, though! (Laughs) But there was a deeper reason behind it. Placing the half-pipe actually solved three major challenges we were facing at the time, all at once.

Three at once? What challenges were they?

Konishi: Our biggest struggle was that the slam dunk action lacked analog feel at the time. The way it worked was, if you moved under the goal and swung the Joy-Con 2 controller upward, your character would automatically jump and perform a dunk. We'd put so much effort into making the two-dimensional movement feel analog, but when it came time to dunk, the whole vehicle just suddenly launched into the air, which felt abrupt.

Ikejiri: We spent a lot of time deliberating how to design it so it didn't feel out of place. At one point, we even considered attaching a giant spring to the wheels so the whole thing could bounce up into the air.

That definitely stands out as being abrupt compared to the other actions.

Konishi: Once we'd placed a half-pipe under the goal, players could jump and carry the ball to the hoop much more naturally. In the end, we designed it so you can pull off a dunk shot by swinging the Joy-Con 2 controller just as you reach the basket.

Hamaue: You need to enter the half-pipe with enough speed to lift off the ground, and at just the right angle to reach the hoop. Just jumping anywhere while swinging the Joy-Con 2 controller doesn’t trigger a dunk. It only activates when you swing it near the hoop, which helped us achieve a satisfying analog feel.

I see. So, the stylish dunk shots, one of the game’s defining features, wouldn’t have been possible without the half-pipe concept.

Konishi: Exactly. The second challenge, which I briefly mentioned earlier when talking about the gravel outside the court, was that players couldn’t immediately return to the center of the court after taking a shot. But once we'd added the half-pipe under the basket, even if a player kept moving straight after taking a shot, they could ride up the slope and come back down, making it much easier to return to the center of the court.

Ikejiri: In this game, the match doesn't stop when points are scored. In most sports, the match halts and resets after one side scores. But in this title, the game carries on without interruption. That means even if the other team scores, you can grab the ball right away and launch a fast break toward their basket. Because the action keeps going, players feel a sense of urgency that makes them want to shout, “Get back on defense!”

Konishi: The third challenge we faced was figuring out how to approach character design. We were still exploring what the playable characters would look like and hadn't settled on a clear direction.

Ikejiri: But once we'd introduced the half-pipe, the game turned into a more acrobatic sport where players could jump high and even tip over if they missed a move. We figured that with gameplay like this, the characters would need helmets and armor. That led us to the current character design.

I see. So, even if it meant going against the team’s initial plan, placing the half-pipe ended up solving all three challenges at once. Speaking of character design, players can choose from three different character types in this game, right?

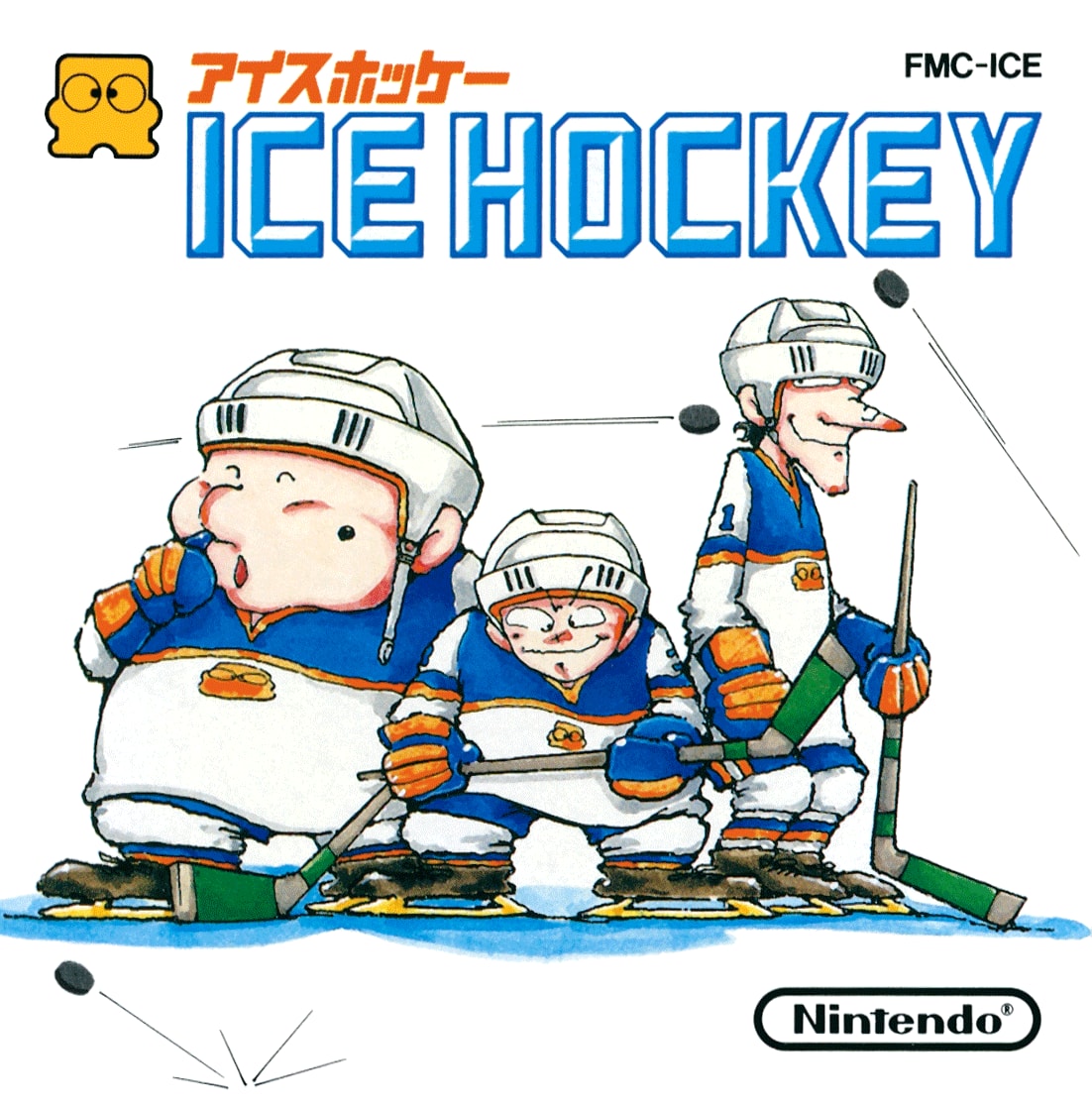

Konishi: From the early stages of development, we had the Famicom Disk System game Ice Hockey (9) in mind, and we planned to have three types of characters.

If there were only one type of character, player skill would more directly determine the outcome of a game. But having characters with different abilities creates opportunities for trial and error and strategic thinking, such as “This team had several Centers, but that team had more Forwards,” or “Maybe next time we should try a different combination.” We thought it would allow matches to unfold in a variety of different ways depending on the players' ideas.

(9) A sports game released in 1988 for the Famicom Disk System in Japan and the Nintendo Entertainment™ System in North America. Players select the physiques and formation of four skaters and aim to score as many points as possible on the ice.

Hamaue: When the team was playing the game during development, there was a time when many of us preferred using the Guard character, who has a smaller physique and can turn quickly. But when we had one large-bodied Center among many Guards, that player could really shine, using their extra weight and height to grab the ball more easily. The well-balanced Forward type could also adapt to the opposition's mix of characters to help steer the game according to the situation.

Konishi: Team composition and strategy can dramatically change how a game unfolds, so I encourage players to experiment and find a play style that suits them best.

So, it’s not purely about skill — team composition, strategy, and character synergy all play a role in how matches unfold. How did the designs for the three character types come together?

Ikejiri: We wanted to make sure players could easily tell which character types were on the court during a match, even from a distance. Since players make vigorous upper body movements to control their wheels during matches, it was difficult to distinguish between character types from afar. Plus, while the three character types have different acceleration and turning abilities, they all share the same top speed.

That’s why we didn’t want to oversimplify them as “light and fast” or “heavy and slow.”

For example, the large and heavy Center can reach the same top speed as the small and light Guard by propelling the wheels with strong, burly arms. We carefully considered how each character should move and look on the court to make them visually convincing. In the end, we incorporated design elements from real-life sports wheelchairs to help express those differences in ability. Each type of sports wheelchair is tailored to the specific needs of its sport. For the physically strong Center, we added features inspired by wheelchair rugby, such as a metal bumper on the front. The well-balanced Forward draws from wheelchair basketball, while the agile Guard uses design elements from wheelchair motocross. By incorporating features from various sports, we were able to distinguish the characters clearly and make their roles easy to recognize.

Guard, Forward, Center

Are the sound effects different for each of the three character types when they move?

Yoshida: Some of them are. When creating sound effects, we keep in mind that players intuitively link sounds with specific actions, like “this sound plays when I move like this.” So, it's tricky to make completely different sounds for each character. Still, we wanted to introduce some variation, so we decided to differentiate the characters' sound design based on each of their weights. Landing after a jump from the half-pipe is one of the most satisfying moments in this game, so we fine-tuned the landing sound effects so they sound just right based on each character’s weight.

Ikejiri: In fact, we deliberately held back on giving the characters in this game individual personalities. Instead, we aimed for a design in which the player’s own gestures, play style, and techniques become the character’s personality, and that uniqueness is directly conveyed to other players around the world.

Konishi: Maybe you'll pull off a slick shot by dodging your opponent with a quick turn, or set yourself up near the three-point line, waiting patiently for the perfect moment to take your shot. However you play, we hope you'll keep honing your skills and let your personality shine through.

On a related note, I understand that landing a trick shot gives you a small bonus compared to a regular shot.

Konishi: Before we'd added that bonus, we were testing the game and noticed a difference in mindset between players who focused on winning and those who prioritized tricks. Those focused on winning wanted their teammates to go for a solid two-point shot rather than to risk botching a more difficult trick shot. We decided to add a bonus based on the trick's difficulty, so even players focused on winning could see the value of going for a trick shot. Winning is important, of course, but we also wanted players to enjoy the thrill of landing cool shots and bringing heat to the court, just like in street basketball. Since trick shots with bonus points can affect the outcome of a game, I think the difference in mindset between those two types of players has diminished.

Read more in Part 3: Park vibes